|

By Scott  I remember the first time I visited Emerson Commons. I remember thinking, "Yes! We found our home!" Since 2014, my wife (Anna), our daughter (Ezra), and I had been renting an apartment in Takoma Village Cohousing in Washington, DC, searching for a cohousing community in which to buy our first home. As a certified city-dweller, I also remember thinking "I can't believe how amazing this property is! A creek and a pool and a view of the mountain!" I'm sure I had a bunch of other exclamation-filled thoughts on that first day, too. But there's one thing I'm pretty sure I did not think. I did not think, "You know what? Two families, each with kids, each with pets, could totally live in the common house together while these houses get built. That's so obvious. We should find other city-dwellers to live with us, people who won't be put off by our total ignorance of home construction, land use, and basic table manners, in large part because they, too, seem to be totally oblivious to these types of things. That would make a ton of sense and be really easy." And yet, here we are. In between that first visit and today, Peter floated the idea that our cohousing experience and immediate need for housing might present a great opportunity for Emerson Commons. Would we be interested in living in the common house? We were thrilled to have our daughter start going to Crozet Elementary right away, and jumped at the chance. (If I'm still allowed to blog after this post, I'll share more about how much we love that school.) The more we thought about moving into the common house, though, the more we wanted it to feel like part of building the larger community. Couldn't the common house be home to other Emerson Commons members? We reached out to Laura and Steve, and their sons Heath and Sullivan. I think our first conversation went something like this: "Shouldn't we all live in the common house together?" "No." "No way." "You're saying 'shouldn't' like 'we shouldn't,' right? Like we should not. Should not we live in the common house." "Yeah, no, I know! It was a joke! Total joke. No way would we do that." "Dad, can we watch a movie tonight?" "THIS IS A SERIOUS CONVERSATION THIS IS NOT ABOUT WATCHING MOVIES!" [Babies crying, mild commotion, slow return to calm] "What were we talking about? "Living in the common house together." "Oh. Totally. We're in. Seven people? Seven beds. Duh. No need to even visit again and think about how we would do it. No brainer. Let's just e-mail each other until we stop thinking about it." By the end of April, we were all moved in, and we love it. We think. At some point last week, once we stopped being so awkward, we decided that we should share some of our experiences on the Emerson Commons blog. Our hope is that in addition to Peter's musings on cohousing and Emerson Commons' members' posts about their own paths to Crozet, we can provide a semi-frequent dispatch from the common house, as we navigate the move from the big city, watch our homes get built, and try to figure out which dining room to use for which meal. And keep a few chickens. And make sure the frog in that picture has been set free.

0 Comments

By Peter Lazar When people are asked what’s most important in life, they will respond with words like “Happiness,” “Relationships,” “Health,” and “Purpose.”

But when people make the most important purchase of their life, which is their home, why do they apply different values? We shouldn’t be measuring “Cost per square foot” but rather “Happiness per square foot.” Try this Home Happiness Calculator to see how your home and immediate neighborhood contribute to your happiness: http://www.emersoncommons.org/home-happiness-calculator.html By Peter Lazar  This Thanksgiving break, I’ve been especially grateful for my cohousing bubble. When I drive home in the dark at 6pm after a long business trip, I look up the hill and appreciate seeing the lights on in the common house. My worries and concerns of the external world stay outside the door as I join the impending common meal. Like catching a cold, I think I’ve caught a bad case of negative worldview from the news and media that I have consumed. It’s gotten so bad that I’m sometimes up at night. I think the cure might be a delicious hot bowl of my neighbor Stephanie’s soup and some good conversation. I’ll venture to say that my neighbors, and perhaps most cohousers, generally share a positive view of humanity. Our approach to living is predicated on it. Otherwise, how could we trust a decision-making model where anyone can “block” a decision? But it all works because we trust each other to place “relationships” over the quickest route to “winning”. We are not only tolerant of but have a true interest in other peoples’ viewpoints because they make for a better, more inclusive decision. In our meetings, we explicitly agree to treat each other with respect. This carries over to daily interactions with each other. Rather than building walls, we both literally and figuratively tear down fences. Our homes foster privacy, but their closeness and orientation towards each other and common spaces creates community. We welcome diversity. Cohousers are fundamentally environmentally conscious. Our buildings are green. We cluster our homes. We drive less. We have organic community gardens. We are typically not ostentatious and status conscious. We believe in living simply. We have smaller homes, share common spaces and share tools, to name a few things. In cohousing, there is no need to covet thy neighbor’s lawnmower because you can always borrow it. I am so grateful that my fellow cohousers don’t share the dark and scary worldview that I see on the screen. If the news is getting you down, turn it off, go outside and appreciate the wonderful like-minded people living around you.

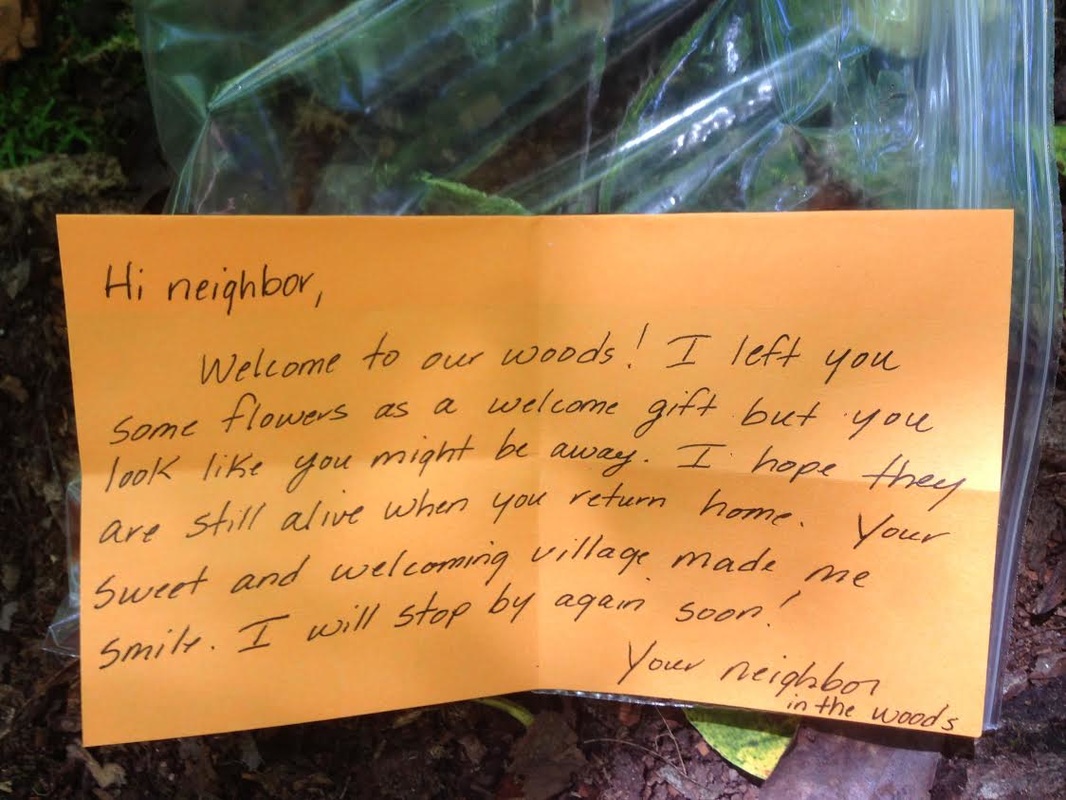

Hi neighbor,

Welcome to our woods! I left you some flowers as a welcome gift but you look like you might be away. I hope they are still alive when you return home. Your sweet and welcoming village made me smile. I will stop by again soon! - Your neighbor in the woods After reading it through a few times, I ran back to the people-sized village to find Ally. We brought the note to the kid’s room in the Common House and began our response. I folded an origami envelope while Ally wrote the letter (her handwriting is only about a billion times neater than mine) responding to the mysterious “neighbor in the woods”. We wrote about how our village wasn’t quite done yet and how we were excited to see other people appreciate our work. We left out a few details, like the not-so-important fact that we are indeed human, and our names. It’s funner not to reveal your identity, right? Ally and I posted the note on the tree, and made a little ladder leading up to it to indicate fairies. Then we waited. A few days letter, we got a response and another gift. The gift was a hand-made wooden fairy swing that I set up by the Redwood Village playground. The orange note included a poem, and revealed the person’s name as Fiona. We assumed it was a pseudonym, because there’s no Fiona living in our neighborhood. Ally and I hand-felted some mushrooms to give to our amazing note-giver, along with another letter. The correspondence has continued since then, and this is one of those times that I feel like the luckiest person on earth because I live in cohousing. I can’t imagine anything this magical happening without the awesome friendly neighbors I have. Ally and I await our next response! By Peter Lazar Cohousing neighborhoods in the U.S. feature consensus for making decisions. You might think:

Example cohouser projects achieved by consensus include big things like deluxe game rooms, exercise rooms, workshops, and greenhouses. My neighbors successfully approving a pool is a great example: The biggest problem with building a pool in an existing neighborhood is the cost. People happily bought their houses without a community pool. Some of them have no interest in a pool. Asking them to spend thousands of dollars for something they will never use seems hopeless. I doubt that a regular 33 home neighborhood would attempt building a community pool. There probably wouldn’t be the social cohesion to embark on such a costly project for so few homes. But let's consider if such a neighborhood does try, and holds a regular majority-rules vote. Say it passes by majority but not unanimous approval. Without buy-in by all, this could lead to a disaster. There would be at least a few extremely unhappy homeowners angry at the other neighbors for being forced to pay a large assessment. That neighborhood might fracture and lose these people from community life. But cohousers are a special breed. They are willing to take on big projects and invest the effort to make sure everyone is happy. Consensus helps get things done. At Shadowlake, the people who wanted a pool started by hosting a series of “salons” on the topic. These are meetings, open to all, where neighbors discuss their ideas and thoughts on a topic. The point of a salon is for each person to be heard. For this reason, each person can freely speak their mind without rebuttal or argument. No one speaks twice until everyone has spoken. Salons are not a time for decision making - they're a time for hearing each others' perspectives. The pool proponents also sent out surveys. Via surveys and salons, the Shadowlake pool proponents learned the details of why some opposed the pool. The anti-pool neighbors learned why others thought having a pool was so exciting and important. The consensus process involves foundational upfront work absent from regular democratic processes. Counterintuitively, the desired or even typical outcome is not compromise. Rather, the upfront sharing of opinions and ideas helps people craft a better “third way”. The “third way” for the Shadowlake proposal is a solution where everyone can use the pool, but not everyone has to pay for construction. Impressively, voluntary pledges covered the pool costs. But management of the pool would be via the regular governance structure. Deeper understandings gained from the consensus process also build connections. We better understand our adversaries. Consequently, we are more willing to incorporate their viewpoints into a solution that satisfies everyone. In Shadowlake's pool example, the pool proponents and detractors all came out happier than where they started. Now, do you still wonder how consensus doesn't continually end in stalemate? In the 11 years I have lived in Shadowlake Village, I have heard of only two cases where someone blocked a proposal and the community resorted to majority vote fallback. The upfront work prevented such situations. People don't usually go forward voting for items that would damage relations with their neighbors. Usually, they find ways to morph a proposal into something more acceptable and better. How do you compare the results of Shadowlake's governance by consensus with the results of the US Congress? If we could all be forced to better understand each other, perhaps we could find better ways to get things done for the greater good. By Peter Lazar "Free-range Parenting" is a recent term for a style of parenting that was long the norm. In his 1946 bestseller, Dr. Benjamin Spock advocated allowing children levels of independence in accordance of their age of development. Parents still know that kids are happier and develop better when they are given freedom to explore and learn from their own mistakes. But sometime after the 1980s, fearfulness and helicopter parenting became normal in the US. We know that letting kids have the run of the neighborhood is good for them, but there's still this parental fear. Why's this?

Crime rates in this country have actually declined by 50% or more since 1993. Many of us with children live in safer neighborhoods with better neighbors than even we did as children. Truly the Internet is part of the problem as we hear dreadful news from around the world. But we saw such news in the 1970s and 80s on TV as well. The problem is more immediate to our surroundings: many of us don't know our neighbors! We logically know that the folks five doors down are fine upstanding people. But because we both work and they both work and we enter our homes via our garages, we've really not had a chance to get to know each other. But viscerally, we worry about letting kids loose. Why's that? I think an intuitive worry is justified in a disconnected neighborhood with upstanding citizens who don't know each other. We think the problem is child abduction but it is more complex and realistic. Molly and I experienced a small example in our cohousing neighborhood last week: An adult neighbor mentioned to Molly that he saw one of our daughters jumping over the nets that block out the traffic (kind of like a tennis court net). This could be slightly dangerous behavior to the kid. I feel that if the neighbor didn't know us well, then he wouldn't have mentioned anything because this is not serious and doesn't harm anyone. But he was comfortable with us and easily expressed his concerned about her welfare. We appreciative he spoke out. This is just one of many unplanned and unexpected interactions that help promote safety. We know each other and look out for one another above and beyond the call of duty. Being pedestrian oriented, there are also a lot more people, including adults, about at any given time. For those of us who grew up as free range children, perhaps in the 1970s and 80s, I think our parents justifiably didn't have the fear parents do today. Perhaps due to single family incomes, there were enough people knowing each other about to provide an extra safety net. Living in cohousing, one thing I don't worry about is what my kids are up to in the neighborhood for hours at a time without me. They have been running in packs together since the age of four or five. My wonderful well-known neighbors are like a protective blanket providing comfort with their collective watchful eyes and participation.

This time I was determined to win the swing-jumping contest. I swung so high that I was horizontal with the support bar. Then, I jumped. The jump must have looked spectacular; it was what we called a “moon jump”. I guess the jump was spectacular, except for the landing part. I had never really believed that people could feel things in slow motion, but I captured all of the moment mid-jump: the smell of cherry blossoms, the taste of air, the feeling of flight, the sound of Kaden screaming, and the sight of the ground. I landed on wood and (surprise) broke my arm. I began crying and ran back to my house. Three different adults came running and asked if I was okay, but I kept running with one destination. Once at my house, I tried not to cry. I didn’t want to tell my mother what had happened. All I wanted was for someone to read me a story.

It turned out I had broken my humerus, right at the elbow. I needed surgery and three pins. What would follow was the most painful month of my life. Yet the month that followed connected me more to people, and helped me think about the goodness of the people around me. Once my mom realized (despite my attempts otherwise) that I had broken my arm, she took me to an emergency care center. Since my sister Mia was old enough to be home alone but needed to be comforted, our neighbor Michael took care of her while I was gone. The people at the place jerked around my arm with such carelessness that I was afraid it would fall off. Finally we went home and I eventually got some sleep. The next day, the cards from my neighbors began arriving. First a card from Michael came and I was delighted. This particular card featured a cat (my favorite animal) and told me to get well soon. I was so happy that Michael had taken care to write to me that I took out my own pencil and stationary. I wrote a card back to him saying how the card helped me so much. That day I stayed home from school and the cards kept coming in from all of my neighbors. I wrote a thank-you card back to every single one of my neighbors, along with little drawings of cats and flowers. Every ten minutes I would get up and run to our mailbox to check for new mail; it was the only thing that kept me distracted from the pain of my arm. The day after my injury I got more than 10 cards! More than half of those cards were yellow (my favorite color) or included cats. I was thrilled. The day after that I had surgery. The pain was almost unbearable, and what kept me from being absolutely miserable was the consideration and kindness of my neighbors. A few of them carried out whole letter-conversations with me. One nice neighbor even wrote a card to Mia complimenting her on how good a sister she was to me, since he knew I was getting all of the attention. By the time of my recovery, I had a whole wall covered with cards. Some important parts of cohousing are the architecture, the car-free zone, and the common house, but it’s the people that really make it a magical experience. By Ava Lazar (age 145 months (132 of them in cohousing)) Originally posted on cohousing.org question-- the one question I can’t answer. The truth is, I don’t know what it’s like to not grow up in cohousing. There are obvious differences, like the lack of roads, the close houses, and the friendly people, that even I understand. But I can’t imagine not knowing everyone in my neighborhood or not being able to step out the front door and wave to the amazing people out there.

When I was about six, I realized that most other people do not have personal connections with the people around them. My friend Zoe came over and was impressed by the neighbors hanging out on each others porches. That particular day held a community potluck and I remember Zoe looking around at all the conversation and happiness and food. She asked whether she could stay forever. That was when I realized I wanted to stay forever too. In the future, I plan to share stories here that are about my life in cohousing. By Peter Lazar Here are my kids on the 4th of July when they were a lot younger with a bunch of neighbor kids. I have to say, our little neighborhood fireworks were even more fun than the big fireworks in the town. Just take a look at the kids' faces!

Notice the ribbons and decorations on the bicycles in the back. Every year we celebrate the Fourth of July with the same tradition. Adults bring refreshments to the common green and set up the sound system in front of the Common House. Kids elaborately decorate their bicycles and scooters with ribbons, pinwheels and flags. Then we kick it off with john Phillips Sousa Stars and Stripes on the speakers while the kids parade on their bicycles in a big loop. Parents and other adults cheer them on. Some of the kids are very tiny. They all have a blast. Afterwards, we all have watermelons and refreshments. This is followed by an afternoon community softball game. In the evening, we have the neighborhood fireworks. Some neighbors then head to town for the big fireworks, but many continue to hang out in the neighborhood. I see little need for the big town fireworks as I'm having so much fun in my community. That picture was taken 9 years ago and the tradition remains unchanged today. There is a new generation of very little kids and the adults and now-preteens and teens still participate. No doubt every neighborhood has its own unique traditions. Traditions are part of the glue of community. By Peter Lazar  New Urbanism purports to solve the loneliness and disconnection that plagues our car-centric suburbs. The theory is that traffic problems will be solved and people will start to interact if you just remove the cul-de-sacs, cram the houses close together with friendly porches and move the cars to alleys in the back. But when I drive through a brand new New Urbanist neighborhood on a beautiful Friday afternoon at 5:30pm, the front porches are empty. I see nobody interacting in front. Where is everyone?  I see a car drive by and follow it. It goes behind the house into an alley. A garage door magically opens and the car drives in. The person has entered his house from a tunnel. By not walking by neighbors' houses, he has missed the opportunity to chat a bit. Such 5 minute encounters build up social capital that leads to more meaningful relationships. And were do the kids play? I should have taken a picture, but I was driving by one of these places and I saw the kids rolling around back on their bigwheels. Where can the parents and their friends hang out and watch? There are porches in front, but there’s no place to play there. So here’s the solution: Move the cars to the periphery, and put the people in front! This is a typical cohousing neighborhood with a pedestrian-oriented street. And here’s another cohousing neighborhood with a pedestrian plaza. Notice all the people hanging out. That's a typical afternoon in cohousing. This is how we should design our neighborhoods.

First Photo: BeyondDC, Creative Commons attribution license Second Photo: Brett VA, Creative Commons attribution license Third Photo: David Shankbone, GNU Free Documentation License Fourth Photo: Sunward Cohousig. Mconavon, GNU Free Documentation License

were not those with the greatest relative parent happiness. Rather, according to the study lead, Dr. Jennifer Glass of the University of Texas, "Policies that made it less stressful and less costly to combine child rearing with paid work “seem to be the ones that really matter.”

A New York Times article about this study went further through interviews to conjecture that in the U.S., there is an incredible anxiety about parenting for a number of reasons. We don't have the support networks. We have to compete for activities because a child's entire fate seems to depend on going to the right college and so many factors lead to that. We are constantly afraid of abductions. We worry about our kids being hit by cars. The article interviews Christine Gross-Loh, the author of “Parenting Without Borders,”. Gross-Loh says “In Japan, my 6-year-old and my 9-year-old can go out and take the 4-year-old neighbor, and that’s just normal,”. In the United States, of course, that kind of freedom usually draws heavy criticism and can even lead to interventions by Child Protective Services. Living in a cohousing neighborhood, where my kids were free to roam the neighborhood in packs by age 4, I feel like I'm definitely outside the norm. With cars out of the picture and in knowing all our neighbors, I could feel safe to do so. My neighbors with young children free up time for each other sometimes by taking turns watching each others' kids. And a short walk away are several teens and preteens who are happy to babysit and don't have to drive over to do so. Photo by Watchcaddy, Flickr Creative Commons Front-facing kitchens, standard in cohousing, build community. You look out your kitchen window while cooking or cleaning dishes and see the action. If you see someone you'd like to talk with or something fun happening, you can put down those dishes and go outside. But that same kitchen in front enables a very private living room in back. With living rooms in back, cohousing homes are more private than typical clustered houses.

Some New Urbanist neighborhoods have homes where the back windows face windows in other homes. Sometimes there's only a garage and no yard out back. The developers just want to pack as many houses onto postage stamp yards as possible. But a typical cohousing neighorhood, built for lifestyle over profit, often has a very private back yard with beautiful scenery and little ability to see neighbors. When you sit on a cohousing front porch reading a book, it's fair game for a neighbor to start a conversation. That's part of the reason you are there. But if you're on your back deck, it's a cultural taboo for anyone to yell up and say "hello." Perhaps one reason that cohousers recognize the importance of privacy is that so many of them are introverts. If you're not living in cohousing, you might be surprised to learn that Myers Briggs tests repeatedly find the majority of cohousers are introverts. There are indeed many extroverts, but there are generally more introverts. As an introvert myself, who also likes people, I find cohousing the perfect balance. I have plenty of privacy when I need it. And when I'm in a mood for community, it's so easy and simple. There are regularly-scheduled meals and events every week. This means I can show up if I feel social. But the events will happen with or without me. Unlike a party invitation where I feel bad if I don't show up, there is no expectation for me to be at these regular events. In cohousing, you can have a social life on your own terms and at your own time when you are feeling social. Furthermore, spontaneous events happen all the time. You can be swept up in the moment of something fun and unexpected that you didn't have to plan yourself. I think many extroverts don't see a need for cohousing. They can live happily in an isolated house because they have the natural energy to go out and make social things happen. Extroverts have an inclination to create community wherever they go. However, it is my belief that both extroverts and introverts live more happily in cohousing than in isolation. And not only community but privacy is fundamental to the equation. My cohousing neighborhood, Shadowlake Village, provides a special benefit when I travel. I call it the "Shadowlake Village Home Monitoring Network".

I can remotely control the temperature in my home, so that several hours before returning from a vacation, the AC or heat is turned on hours before I arrive back. The technology is quite simple: I just call a neighbor to do it! And I'm happy to do the same when a neighbor travels. The Cohousing Home Monitoring Network makes traveling easier in other ways:

The Cohousing Home Monitoring Network is just one of many benefits from knowing your neighbors.

“It is not the length of life, but the depth.”

“The purpose of life is not to be happy. It is to be useful, to be honorable, to be compassionate, to have it make some difference that you have lived and lived well.” “For every minute you are angry you lose sixty seconds of happiness.” “Guard well your spare moments. They are like uncut diamonds. Discard them and their value will never be known. Improve them and they will become the brightest gems in a useful life.” “It is one of the most beautiful compensations of life, that no man can sincerely try to help another without helping himself.” “Enthusiasm is one of the most powerful engines of success. When you do a thing, do it with all your might. Put your whole soul into it. Stamp it with your own personality. Be active, be energetic, be enthusiastic and faithful, and you will accomplish your object. Nothing great was ever achieved without enthusiasm.” “To be yourself in a world that is constantly trying to make you something else is the greatest accomplishment.”

My grandmother’s life story relates to this. Well-educated from Hungary, she and her husband fled as refugees to New York City after World War Two with nothing but their suitcases Not knowing the language, they worked on an assembly line in a paper cup factory. My grandfather tragically died at a young age leaving my grandmother alone to raise their children. After a long career and many years saving, she finally achieved her goal of retiring in Florida. She lived the last 15 years in a retirement condominium where an excellent central management took care of yard work, pool maintenance and even arranged social events for the residents. Residents could theoretically live a life of ease. She had achieved her retirement dream, so I thought.

After my grandmother died, I was helping move out her belongings. I came across a book where she had highlighted some passages. The passage described the author's sense of void from her meaningless retirement community life playing cards and wiling way the time without relatives nearby and without a sense of purpose. My charming and gregarious grandmother never complained and I always assumed she was entirely happy in her retirement with her retirement village buddies. So this made me think completely differently and with sadness about her later years. The cohousing lifestyle contrasts to a retirement home life of luxury. In cohousing, everyone, including the retired, cooks and participates in workshare. Even if they can afford to hire others, they do the work for themselves and their neighbors. There is more effort but there is also more reward. By helping their neighbors and in return being helped, they connect with every neighbor, even those that aren’t necessarily friends. And friendships takes an even greater dimension by working together for the greater good of the community. We live a purposeful life by helping others. As Einstein stated above, we are here primarily for the sake of others. Our main life purpose might be volunteering or mission-oriented career. But we gain a bonus extra meaning in our lives when we also contribute to the lives of the people immediately around us. I'm writing this at 34,000 feet on my flight to the 2016 Aging in Place conference hosted by Coho/US in Salt Lake City. I like in-flight wi-fi ! ; but I digress...

The topic of Aging in Place got me thinking about the benefits of living in community as we get older. I think of my former neighbor, Betty, who in her vibrant 80s was an active contributing member and cook for the community. Then she broke her hip. Such a setback at that age could easily have sent her to the nursing home. But her neighbors rallied and took turns bringing her meals until she recovered. She lived quite a while longer in that setting than she could have, living alone. Similarly, the neighborhood recently helped another beloved neighbor as she was recovering from cancer. Key to both of their successes was that they were contributing community members before they got sick. Their years of contributing to the community resulted in appreciation by others who were more than happy to help them in their time of need. One shouldn't move to a cohousing neighborhood when 85 and frail expecting to be immediately cared for by neighbors who are yet strangers. Contributing to a community while a still active 75 year old has an even more important benefit: a life-extending sense of purpose and belonging. I'll close on a negative today. A couple months ago, I took the above picture of an assisted living facility in Crozet. Typical to these places, there are hardly any outdoor spaces for the residents. They’re stuck inside in air-conditioning. And outside are just parking lots and the plain grassy field depicted above. Don't people want to enjoy lovely outdoor spaces when they are old as well!? Cohousing contributes a beautiful community both personally and physically for young and old alike. The above title is tongue-in-cheek but true!

More often than not, after our college days, we become decidedly less social because of all the work to keep up a social life. This is not just because we are busier, but also because of our physical separation. Generally, we can’t just walk outside and be amongst friends like in college. Our car-centric lifestyle has forced our social lives to be more proactive. There’s planning involved before inviting people over. We have to get on peoples' schedules. More spontaneous socializing happens when people live closer together with pleasant outdoor spaces to congregate. Imagine a summer early evening in a small rural fishing village. It can be anywhere in the world - be it Southern Europe, Latin America, Asia or Africa. With the aroma of grilled fish in the air, the men and women of the village socialize outside after their hard day while children run around. This happens in the United States, too, when the car is out of the picture and there are nice outdoor spaces to congregate. It's often when not everyone can afford a car. You see neighbors enjoying each others' company outdoors. It's the same in cohousing neighborhoods. Commonly after work and in nice weather you see a few neighbors sitting on their porches or in a common areas. Eventually more neighbors join them. People bring out drinks and snacks. Someone pulls out a barbeque. Kids run around. Suddenly, you have spontaneous block party with no prior planning. It's the way people have lived for thousands of years and can enjoy today as well. [Photo: Damian Morys, Creative Commons] Traffic safety professionals state that kids shouldn’t cross the street alone until age ten. Why do we design our neighborhoods like this?

So we’d be facing maybe 10 years before our children could expand their zone to across the street without oversight. We're lucky if the kids have a similarly-aged friend two doors down. The kids would need to be even older before we let them ride their bikes off alone to some distant friend’s house. In the meantime, we spend so much of our time arranging play dates and driving our kids back and forth. Cohousing solves this problem. Houses face a pedestrian area and cars are relegated to the periphery. My daughters had the run of our cohousing neighborhood at age 4 with many friends nearby. Kids are running around outside in a pack all day in the after school hours and on weekends. Life is spontaneous and free for these kids from a young age without pre-planned play dates. We know our neighbors, so there's always an adult around or nearby to apply a bandage skinned knee. It's a wonderful outdoor lifestyle that doesn't have to be something from the past. - Peter [Photo by Derek Jensen (Tysto) - Own work, Public Domain] Have you ever felt a “feeling” of loneliness that seems physical and tangible?

Similar to the feeling of hunger, it seems the loneliness feeling serves an evolutionary need: We feel hungry so that we eat and don’t die. Likewise, we physically feel lonely so that we make connections with each other and we can collectively thrive. |

LinksArchive

July 2020

TOPICS |

Contact Us • Emerson Commons Cohousing • 610 Teaberry Lane, Crozet, VA 22932