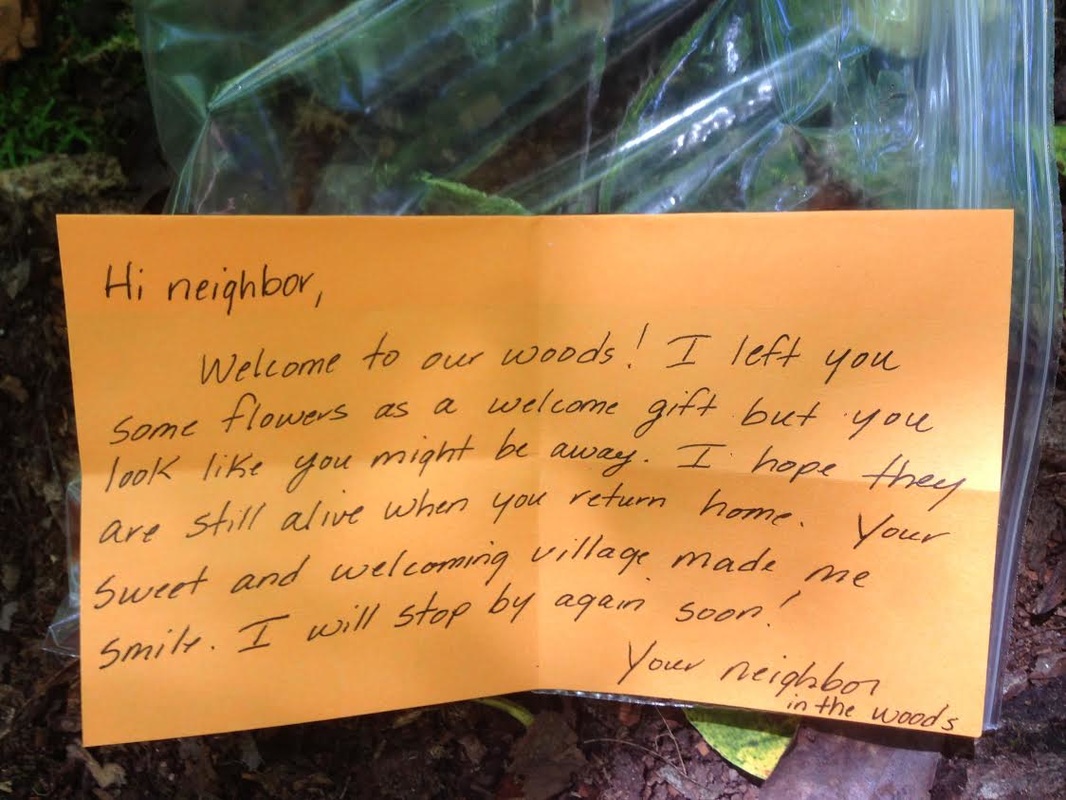

Hi neighbor,

Welcome to our woods! I left you some flowers as a welcome gift but you look like you might be away. I hope they are still alive when you return home. Your sweet and welcoming village made me smile. I will stop by again soon! - Your neighbor in the woods After reading it through a few times, I ran back to the people-sized village to find Ally. We brought the note to the kid’s room in the Common House and began our response. I folded an origami envelope while Ally wrote the letter (her handwriting is only about a billion times neater than mine) responding to the mysterious “neighbor in the woods”. We wrote about how our village wasn’t quite done yet and how we were excited to see other people appreciate our work. We left out a few details, like the not-so-important fact that we are indeed human, and our names. It’s funner not to reveal your identity, right? Ally and I posted the note on the tree, and made a little ladder leading up to it to indicate fairies. Then we waited. A few days letter, we got a response and another gift. The gift was a hand-made wooden fairy swing that I set up by the Redwood Village playground. The orange note included a poem, and revealed the person’s name as Fiona. We assumed it was a pseudonym, because there’s no Fiona living in our neighborhood. Ally and I hand-felted some mushrooms to give to our amazing note-giver, along with another letter. The correspondence has continued since then, and this is one of those times that I feel like the luckiest person on earth because I live in cohousing. I can’t imagine anything this magical happening without the awesome friendly neighbors I have. Ally and I await our next response!

0 Comments

By Peter Lazar "Free-range Parenting" is a recent term for a style of parenting that was long the norm. In his 1946 bestseller, Dr. Benjamin Spock advocated allowing children levels of independence in accordance of their age of development. Parents still know that kids are happier and develop better when they are given freedom to explore and learn from their own mistakes. But sometime after the 1980s, fearfulness and helicopter parenting became normal in the US. We know that letting kids have the run of the neighborhood is good for them, but there's still this parental fear. Why's this?

Crime rates in this country have actually declined by 50% or more since 1993. Many of us with children live in safer neighborhoods with better neighbors than even we did as children. Truly the Internet is part of the problem as we hear dreadful news from around the world. But we saw such news in the 1970s and 80s on TV as well. The problem is more immediate to our surroundings: many of us don't know our neighbors! We logically know that the folks five doors down are fine upstanding people. But because we both work and they both work and we enter our homes via our garages, we've really not had a chance to get to know each other. But viscerally, we worry about letting kids loose. Why's that? I think an intuitive worry is justified in a disconnected neighborhood with upstanding citizens who don't know each other. We think the problem is child abduction but it is more complex and realistic. Molly and I experienced a small example in our cohousing neighborhood last week: An adult neighbor mentioned to Molly that he saw one of our daughters jumping over the nets that block out the traffic (kind of like a tennis court net). This could be slightly dangerous behavior to the kid. I feel that if the neighbor didn't know us well, then he wouldn't have mentioned anything because this is not serious and doesn't harm anyone. But he was comfortable with us and easily expressed his concerned about her welfare. We appreciative he spoke out. This is just one of many unplanned and unexpected interactions that help promote safety. We know each other and look out for one another above and beyond the call of duty. Being pedestrian oriented, there are also a lot more people, including adults, about at any given time. For those of us who grew up as free range children, perhaps in the 1970s and 80s, I think our parents justifiably didn't have the fear parents do today. Perhaps due to single family incomes, there were enough people knowing each other about to provide an extra safety net. Living in cohousing, one thing I don't worry about is what my kids are up to in the neighborhood for hours at a time without me. They have been running in packs together since the age of four or five. My wonderful well-known neighbors are like a protective blanket providing comfort with their collective watchful eyes and participation.

This time I was determined to win the swing-jumping contest. I swung so high that I was horizontal with the support bar. Then, I jumped. The jump must have looked spectacular; it was what we called a “moon jump”. I guess the jump was spectacular, except for the landing part. I had never really believed that people could feel things in slow motion, but I captured all of the moment mid-jump: the smell of cherry blossoms, the taste of air, the feeling of flight, the sound of Kaden screaming, and the sight of the ground. I landed on wood and (surprise) broke my arm. I began crying and ran back to my house. Three different adults came running and asked if I was okay, but I kept running with one destination. Once at my house, I tried not to cry. I didn’t want to tell my mother what had happened. All I wanted was for someone to read me a story.

It turned out I had broken my humerus, right at the elbow. I needed surgery and three pins. What would follow was the most painful month of my life. Yet the month that followed connected me more to people, and helped me think about the goodness of the people around me. Once my mom realized (despite my attempts otherwise) that I had broken my arm, she took me to an emergency care center. Since my sister Mia was old enough to be home alone but needed to be comforted, our neighbor Michael took care of her while I was gone. The people at the place jerked around my arm with such carelessness that I was afraid it would fall off. Finally we went home and I eventually got some sleep. The next day, the cards from my neighbors began arriving. First a card from Michael came and I was delighted. This particular card featured a cat (my favorite animal) and told me to get well soon. I was so happy that Michael had taken care to write to me that I took out my own pencil and stationary. I wrote a card back to him saying how the card helped me so much. That day I stayed home from school and the cards kept coming in from all of my neighbors. I wrote a thank-you card back to every single one of my neighbors, along with little drawings of cats and flowers. Every ten minutes I would get up and run to our mailbox to check for new mail; it was the only thing that kept me distracted from the pain of my arm. The day after my injury I got more than 10 cards! More than half of those cards were yellow (my favorite color) or included cats. I was thrilled. The day after that I had surgery. The pain was almost unbearable, and what kept me from being absolutely miserable was the consideration and kindness of my neighbors. A few of them carried out whole letter-conversations with me. One nice neighbor even wrote a card to Mia complimenting her on how good a sister she was to me, since he knew I was getting all of the attention. By the time of my recovery, I had a whole wall covered with cards. Some important parts of cohousing are the architecture, the car-free zone, and the common house, but it’s the people that really make it a magical experience. By Ava Lazar (age 145 months (132 of them in cohousing)) Originally posted on cohousing.org question-- the one question I can’t answer. The truth is, I don’t know what it’s like to not grow up in cohousing. There are obvious differences, like the lack of roads, the close houses, and the friendly people, that even I understand. But I can’t imagine not knowing everyone in my neighborhood or not being able to step out the front door and wave to the amazing people out there.

When I was about six, I realized that most other people do not have personal connections with the people around them. My friend Zoe came over and was impressed by the neighbors hanging out on each others porches. That particular day held a community potluck and I remember Zoe looking around at all the conversation and happiness and food. She asked whether she could stay forever. That was when I realized I wanted to stay forever too. In the future, I plan to share stories here that are about my life in cohousing. By Peter Lazar Here are my kids on the 4th of July when they were a lot younger with a bunch of neighbor kids. I have to say, our little neighborhood fireworks were even more fun than the big fireworks in the town. Just take a look at the kids' faces!

Notice the ribbons and decorations on the bicycles in the back. Every year we celebrate the Fourth of July with the same tradition. Adults bring refreshments to the common green and set up the sound system in front of the Common House. Kids elaborately decorate their bicycles and scooters with ribbons, pinwheels and flags. Then we kick it off with john Phillips Sousa Stars and Stripes on the speakers while the kids parade on their bicycles in a big loop. Parents and other adults cheer them on. Some of the kids are very tiny. They all have a blast. Afterwards, we all have watermelons and refreshments. This is followed by an afternoon community softball game. In the evening, we have the neighborhood fireworks. Some neighbors then head to town for the big fireworks, but many continue to hang out in the neighborhood. I see little need for the big town fireworks as I'm having so much fun in my community. That picture was taken 9 years ago and the tradition remains unchanged today. There is a new generation of very little kids and the adults and now-preteens and teens still participate. No doubt every neighborhood has its own unique traditions. Traditions are part of the glue of community. By Peter Lazar  New Urbanism purports to solve the loneliness and disconnection that plagues our car-centric suburbs. The theory is that traffic problems will be solved and people will start to interact if you just remove the cul-de-sacs, cram the houses close together with friendly porches and move the cars to alleys in the back. But when I drive through a brand new New Urbanist neighborhood on a beautiful Friday afternoon at 5:30pm, the front porches are empty. I see nobody interacting in front. Where is everyone?  I see a car drive by and follow it. It goes behind the house into an alley. A garage door magically opens and the car drives in. The person has entered his house from a tunnel. By not walking by neighbors' houses, he has missed the opportunity to chat a bit. Such 5 minute encounters build up social capital that leads to more meaningful relationships. And were do the kids play? I should have taken a picture, but I was driving by one of these places and I saw the kids rolling around back on their bigwheels. Where can the parents and their friends hang out and watch? There are porches in front, but there’s no place to play there. So here’s the solution: Move the cars to the periphery, and put the people in front! This is a typical cohousing neighborhood with a pedestrian-oriented street. And here’s another cohousing neighborhood with a pedestrian plaza. Notice all the people hanging out. That's a typical afternoon in cohousing. This is how we should design our neighborhoods.

First Photo: BeyondDC, Creative Commons attribution license Second Photo: Brett VA, Creative Commons attribution license Third Photo: David Shankbone, GNU Free Documentation License Fourth Photo: Sunward Cohousig. Mconavon, GNU Free Documentation License

were not those with the greatest relative parent happiness. Rather, according to the study lead, Dr. Jennifer Glass of the University of Texas, "Policies that made it less stressful and less costly to combine child rearing with paid work “seem to be the ones that really matter.”

A New York Times article about this study went further through interviews to conjecture that in the U.S., there is an incredible anxiety about parenting for a number of reasons. We don't have the support networks. We have to compete for activities because a child's entire fate seems to depend on going to the right college and so many factors lead to that. We are constantly afraid of abductions. We worry about our kids being hit by cars. The article interviews Christine Gross-Loh, the author of “Parenting Without Borders,”. Gross-Loh says “In Japan, my 6-year-old and my 9-year-old can go out and take the 4-year-old neighbor, and that’s just normal,”. In the United States, of course, that kind of freedom usually draws heavy criticism and can even lead to interventions by Child Protective Services. Living in a cohousing neighborhood, where my kids were free to roam the neighborhood in packs by age 4, I feel like I'm definitely outside the norm. With cars out of the picture and in knowing all our neighbors, I could feel safe to do so. My neighbors with young children free up time for each other sometimes by taking turns watching each others' kids. And a short walk away are several teens and preteens who are happy to babysit and don't have to drive over to do so. Photo by Watchcaddy, Flickr Creative Commons Traffic safety professionals state that kids shouldn’t cross the street alone until age ten. Why do we design our neighborhoods like this?

So we’d be facing maybe 10 years before our children could expand their zone to across the street without oversight. We're lucky if the kids have a similarly-aged friend two doors down. The kids would need to be even older before we let them ride their bikes off alone to some distant friend’s house. In the meantime, we spend so much of our time arranging play dates and driving our kids back and forth. Cohousing solves this problem. Houses face a pedestrian area and cars are relegated to the periphery. My daughters had the run of our cohousing neighborhood at age 4 with many friends nearby. Kids are running around outside in a pack all day in the after school hours and on weekends. Life is spontaneous and free for these kids from a young age without pre-planned play dates. We know our neighbors, so there's always an adult around or nearby to apply a bandage skinned knee. It's a wonderful outdoor lifestyle that doesn't have to be something from the past. - Peter [Photo by Derek Jensen (Tysto) - Own work, Public Domain] |

LinksArchive

July 2020

TOPICS |

Contact Us • Emerson Commons Cohousing • 610 Teaberry Lane, Crozet, VA 22932